By Louise Willder, copywriter at Penguin Books and author of Blurb Your Enthusiasm: An A-Z of Literary Persuasion (London: Oneworld Publications, 2022), a Times Book of the Year. An abridged Spanish-language version entitled Cien palabras a un desconocido (Madrid: gris tormenta, 2025) is available here.

The one guarantee about living in a human body is that, at some stage, it will let you down. Our bodies are remarkable things, but they also age, ache, break, change, leak, bleed, scar, get infected and cause us pain. We cannot escape it, and it scares us. Consequently, fear of our bodies, of illness and imperfection, is at the heart of the literature of fear, whether a traditional English ghost story or a fantasy horror novel. ‘Body horror’ is an established genre in film, with directors such as David Cronenberg and Julia Ducournau exploring and exploiting the degeneration or destruction of the physical body with gory glee. But well before this, the same fear of things happening to our bodies ran through supernatural tales: of invasion; of contagion; of transformation; and of mutilation.

Ghosts in some shape or form have been appearing in literature since the Epic of Gilgamesh, but peaked in popularity with the heyday of the British ghost story, lasting roughly from the mid- to-late-nineteenth century (partly due to the rise of serialisation in periodicals) until the mid-twentieth century. It is a form of storytelling designed to provoke a physical reaction in the reader; a close cousin to Victorian ‘sensation fiction’, which encompassed crime, mystery and horror. I have been a copywriter in the publishing industry for over twenty-five years, using words to try to persuade readers to buy other people’s words, and I am fascinated by the language of emotion, and of fear in particular. Writers aim to express and to cause fear not simply by setting up scares, but by creating a visceral shudder in the reader through physical, sensory detail: we experience and mimic the sensations we read about. Lafcadio Hearn, the esteemed Irish re-teller of Japanese ghost stories, wrote in his 1900 autobiographical tale ‘Nightmare-Touch’, ‘the common fear of ghosts is the fear of being touched by ghosts’.[1] The supernatural tale is the most corporeal of genres, expressing bodily terrors that are both timeless (the cold, unknown hand in the dark), and of their time.

We even use the vocabulary of illness to describe the effect of a ghost story on us: a tale is chilling; it will make us shiver or shake or quake. In Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw (described by one reviewer as ‘sickening’), the governess talks of ‘a sudden sickness of disgust’ and ‘the grossness’, as her feverish charges become increasingly agitated by diabolical visitations, and her own sanity cracks.[2] (There is also a tantalising hint in the story’s finale that evil can actually kill us, as at the end of Edith Nesbit’s story of a cursed family, ‘The Shadow’). The moral corruption of children is embodied in the language of physical repulsion. There is a sense here not just of fearsomeness, but of impurity, or unwholesomeness (a literal translation of the German word for ‘the uncanny’ as Freud described it, unheimlich, is ‘unhomely’).

Sickness is more than a metaphor in ghost stories, however. In some tales, the supernatural can make us ill. The first pillar of body horror is the fear of invasion: of something alien entering our bodies. As author Michael Newton says of the genre, ‘The spiritual intrudes on the physical, in so doing becomes correspondingly physical itself’.[3] This can be seen in Margaret Oliphant’s 1882 tale ‘The Open Door’, where a father away on business receives a telegram saying his young son Roland is dangerously ill with ‘brain-fever’, and finds him deathly pale, possibly hallucinating, with eyes ‘like blazing lights’.[4] It transpires that Roland has seen a ghost. Roland’s fear – which turns out to be of a relatively benign ghost – has manifested itself as physical infection. This bodily invasion is far more deadly in Margery Lawrence’s 1922 tale ‘The Haunted Saucepan’, in which the new tenant of a central London flat boasting an excellent cook and (suspiciously) low rent is seized in the night by excruciating pains, like ‘some ghastly acid that was burning my very vitals out’.[5] With the help of a doughty sidekick, he discovers that the flat’s former owner was a femme fatale who poisoned her husband and a succession of lovers – and whose malevolent spirit continues to do so. Similarly, in Guy de Maupassant’s vampiric ‘The Horla’ (whose title is thought to be a portmanteau of the French words hors and là; ‘out there’), the blithely unaware narrator salutes a ship he sees on the Seine, only to find himself somehow infected by a spirit from within it, which results in ‘a strange malaise’, as if ‘an unbearable weight was lying on my chest and another mouth was sucking the life out of me through my own’.[6] The invisible creature haunts his nights and drinks the water on his bedside, until he fears it is a new form of life that may take over the whole of humankind.

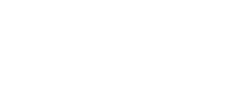

With the vampire story, our fear of contamination is coupled with the terror of contagion. Dracula, 1897, is overripe for interpretation (one critic Maurice Richardson described it as ‘a kind of incestuous, necrophilous, oral-anal-sadistic all-in-wrestling match’),[7] and has been seen as embodying anxiety around foreigners, women, sex, menstruation, queerness and the working classes, among other things. According to Paul Barber’s book Vampires, Burials and Death, the vampire story originated not in folkloric monsters, but in the behaviour of the human corpse after death, as it moves, makes noises and excretes fluids, leading to the ancient myth of ‘the undead’ in cultures all over the world. To many critics, the idea of Bram Stoker’s novel expressing very real Victorian fears of syphilis has been a seductive one (there is speculation that he may have died as a result of the disease). The terror in Dracula stems not just from foreign bloodsuckers invading our bodies, but of the infection spreading across the world, so that, as Van Helsing says, the forces of good must ‘sterilize the earth’.[8] When Mina has been attacked by Dracula, she fears she has become untouchable to her fiancé Jonathan Harker: ‘Unclean, unclean! I must touch him or kiss him no more’.[9] Harker, meanwhile, has already been tempted by three female vampires, with their red lips and ‘a deliberate voluptuousness which was both thrilling and repulsive’.[10] A notable flip side of this fearsome female sexuality is Sheridan le Fanu’s 1872 novella Carmilla, where a young woman, Laura, is torn between desire and terror of her vampiric female lover. This precursor to Dracula employs the same images of bodily invasion and parasitism, but embraces the feminine rather than abhorring it.

The fear of transformation, of being physically changed in some way by supernatural forces, is the third tenet of body horror, and can be seen in everything from werewolf myths to Gregor Samsa waking up to discover he is a cockroach (or an insect, or vermin, depending on which translation of Metamorphosis you read). In ghost stories, bodily transformation often has a moral purpose: as Stephen King wrote, ‘Within the frame of most horror tales we find a moral code so strong it would make a Puritan smile’.[11] Robert Louis Stevenson’s terrifying 1881 tale ‘Thrawn Janet’, written in Scots dialect, is the story of a woman who is in league with the devil. She is struck by some kind of affliction, and appears ‘wi’ her neck thrawn, and her heid on ae side, like a body that has been hangit, and a girn on her face like an unstreakit corp … frae that day forthshe couldnae speak like a Christian woman, but slavered and played click wi’ her teeth like a pair o’shears’.[12] What sounds to us like a stroke is the manifestation of Janet going to the dark side. (Sadly, the use of physical disfigurement as a sign of moral decay is not one that has left us, as anyone who has seen a James Bond villain on film will testify). W. W. Jacobs’ ‘The Monkey’s Paw’ (1902) is another masterly supernatural tale where a body is changed in horrifying ways, this time the resurrected corpse of a beloved son, who, in a grieving mother’s cursed wish, is summoned from the grave after being mutilated beyond recognition by an industrial accident. As her terrified husband says, ‘I could only recognize him by his clothing. If he was too terrible for you to see then, how now?’[13] It is a warning against meddling with forces beyond our control; and wishing for what you cannot have.

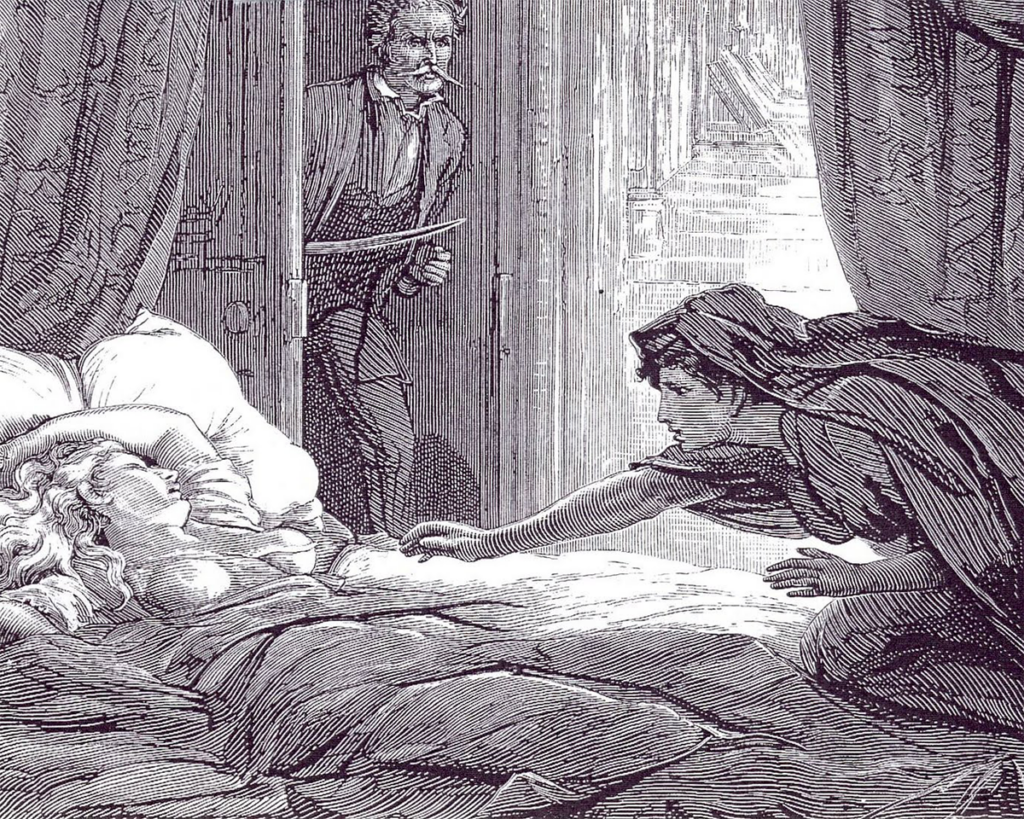

The mutilated, even mutated, human has been central to the science-fiction genre since Frankenstein, and also bleeds into the ghost story. The writings of M. R. James, the King’s College provost who entertained his students with chilling tales every Christmas Eve, publishing them as Ghost Stories of an Antiquary in 1904, are filled with a very particular horror of humanlike creatures, and of the body. His ghosts are not ethereal sprits. They are physical and palpable: skeletal, long-nailed, hairless (or sometimes hairy), spiderlike, a ‘face of crumpled linen’.[14] It is often thought that James’s writing expressed a revulsion at the monstrous feminine – is the ‘mouth, with teeth, and with hair about it’ that one protagonist places his hand in a vagina dentata?[15] There is an undeniable squeamishness in his tales. Yet their protagonists – mostly bumbling bachelors and academics – are also cursed for being dilettantes, for studying too lightly and carelessly unearthing ancient forces they cannot control, rather than pursued by a repressed eroticism. The most physically grisly of James’s ghost stories is ‘Lost Hearts’, in which a young boy, Stephen, stays at the mansion of his elder cousin Mr Abney, and is haunted by the spirits of a young girl and boy who display signs of ghastly mutilation: ‘a terrifying spectacle. On the left side of his chest there opened a black and gaping rent’.[16] We discover that these wandering, homeless children were the subject of a gruesome experiment in black magic; used as guinea pigs by Abney because they could disappear ‘without occasioning a sensible gap in society’.[17] Abney, in an act of macabre poetic justice, is eventually killed in exactly the same way: punished for dabbling in occult forces, and for his callous snobbery.

The literature of fear can take many forms: a battle against a monster, a haunted house, an otherworldly being, a demonic creature, a cursed object. But, as so many ghost stories show, especially those concerned with bodily horror, the greatest danger often comes from human beings.

[1] In Michael Newton (ed.), The Penguin Book of Ghost Stories (London: Penguin Classics, 2010), p. 225.

[2] Henry James, The Turn of the Screw (London: Penguin Classics, 2011), p. 39 and p. 57.

[3] Newton, The Penguin Book of Ghost Stories, p. xxiv.

[4] In Newton (ed.), The Penguin Book of Ghost Stories, p. 169.

[5] In Melissa Edmundson (ed.), Women’s Weird: Strange Stories by Women, 1890-1940 (Bath: Handheld Press, 2022), p. 172.

[6] Guy de Maupassant, Moonlight (London: Penguin Classics, 2023), p. 75.

[7] In Bram Stoker, Dracula (London: Penguin Classics, 2003), p. xi.

[8] Stoker, Dracula (London: Penguin English Library, 2012), p. 281.

[9] Stoker, Dracula (2012), p. 331.

[10] Stoker, Dracula (2012), p. 43.

[11] In Mark Kermode, ‘Jaws, 40 Years On’, The Guardian (31 May 2015), https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/may/31/jaws-40-years-on-truly-great-lasting-classics-of-america-cinema

[12] In Newton (ed.), The Penguin Book of Ghost Stories, p. 155.

[13] In Newton (ed.), The Penguin Book of Ghost Stories, p. 240.

[14] M. R. James, Ghost Stories (London: Penguin English Library, 2018), p. 102.

[15] James, Ghost Stories, p. 25.

[16] James, Ghost Stories, p. 9.

[17] James, Ghost Stories, p. 11.

Works Cited

Barber, Paul, Vampires, Burials and Death (Yale University Press, 1988)

Edmundson, Melissa (ed.), Women’s Weird: Strange Stories by Women, 1890-1940 (Bath: Handheld Press, 2022)

James, Henry, The Turn of the Screw (London: Penguin Classics, 2011)

James, M. R., Ghost Stories (London: Penguin English Library, 2018)

Kermode, Mark, ‘Jaws, 40 Years On’, The Guardian (31 May 2015), https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/may/31/jaws-40-years-on-truly-great-lasting-classics-of-america-cinema

Le Fanu, Sheridan, Carmilla (London: Pushkin Press, 2020)

Maupassant, Guy de, Moonlight (London: Penguin Classics, 2023)

Newton, Michael (ed.), The Penguin Book of Ghost Stories (London: Penguin Classics, 2010)

Stoker, Bram, Dracula (London: Penguin English Library, 2012)

Stoker, Bram, Dracula (London: Penguin Classics, 2003)