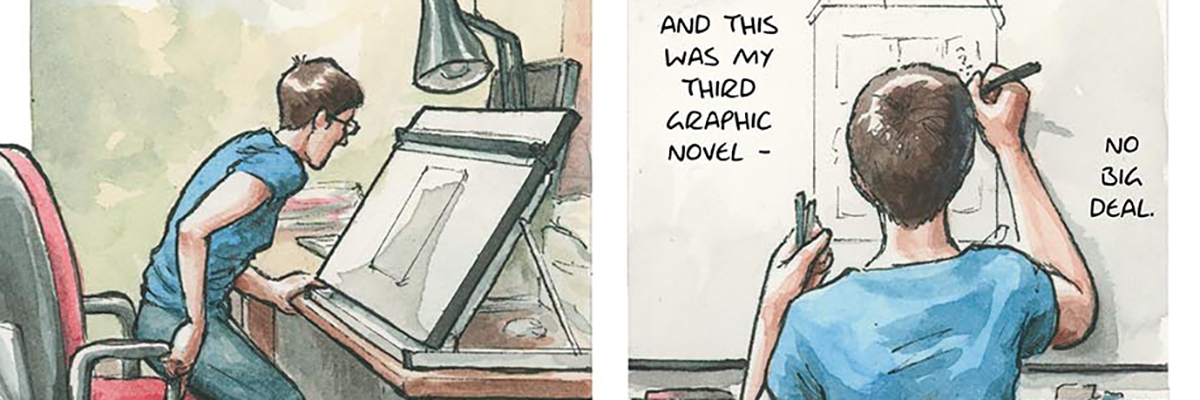

Thank you so much to our participants and speakers for joining our Creative Writing workshop on “Burnout, Overload, and Resilience,” held at the University of Exeter on June 14, 2024. The event was organised by Prof. Katharine Murphy (Principal Investigator for Reading Bodies), Dr. Sally Flint (Lecturer in Creative Writing), and Dr. Olivia Glaze (AHRC Postdoctoral Researcher) and we were thrilled to welcome such a diverse group to the event – which included teachers, entrepreneurs, NHS practitioners, yoga teachers, a live illustrator, academics, and postgraduate students.